The gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. This definition is the thread that ties together the various topics in the present Substack series.

One reason the story of Jesus is significant is that his death and resurrection functions as a work, an atoning work. This work results in the forgiveness of your and my sin. We are justified by God’s grace, meaning that we do not need to justify ourselves.

Here is the point of the present post: because God justifies us, we do not need to justify ourselves. Yet the depth of the human predicament is found in our resistance to the gospel, namely, we want to justify ourselves regardless. Self-justification is the enemy of the gospel.

Classic Lutheran dogmatician Franz Otto Pieper (1852-1931) warned us: “the denial of justification by faith is also destructive and preventive of all Christian knowledge and insight” (Pieper, 1951, Kindle II:11649). Yes, indeed! Now I think Pieper was pitting the doctrine of justification against its doctrinal denial. In what follows I would like to turn to the existential or personal level, where you and I pit our own self-justification against God’s justifying us by divine grace.

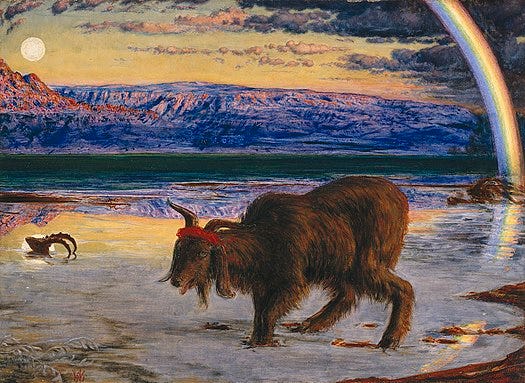

Drawing upon a previous Patheos series on sin, I will try here to make visible the otherwise almost invisible habit we humans have of justifying ourselves and scapegoating others just so we look good. It is this mechanism of self-justification buttressed by scapegoating that blunts, repels, and resists the gospel message. The Holy Spirit exerts great effort to overcome this resistance to the message of forgiveness, justification, and salvation.

What is sin again?

Intellectual gadfly David Bently Hart reminds us of the common understanding of sin. “In the modern world we have a view of sin as a kind of transgression of a moral code. And the corollary of this is ‘original sin’ - the view that we are somehow infected by the Fall with a natural propensity for doing evil not good.” Be careful here. Such a definition of sin mistakenly thinks a feather defines the life of a flock of Canadian geese replete with migration routes, eating preferences, breeding cycles, and combat with coyote predators. This view of sin is so banal as to be misleading.

Thankfully, Hart recognizes how important it is to understand sin rightly. “This is clearly very significant for us Christians to understand well because our gospel is framed as a redemption and ‘sin’ is normally presented as the ‘problem’ that the gospel solves.” Just what is the problem the gospel solves? Sin.

Let me reframe this question: if the significance of the story of Jesus is that we are justified by God’s grace, what problem does this solve? Answer: self-justification. In St. Paul’s writings and during the Reformation the problem was described as works-righteousness. I recommend the term, self-justification, to zero in on why works-righteousness resists the gospel.

So, in light of the gospel, we need to understand the subtle way that sin deforms the human soul while contributing to evil in the world. To evil and sin’s contribution to evil we now turn.

Evil is real, but it does not exist

There is no such thing as pure evil. Evil is always a leech off the good. Being is good in itself, innately good. Evil, in contrast, is the force of non-being that threatens to turn reality into mirage, harmony into strife, existence into non-existence. And, yes, life into death.

Evil does not exist, therefore. Anything that exists stands out from non-being. Our term, exist, comes from the Greek ek-stasis, to stand out as one thing among others. Evil is not one thing among others. Evil is the force of non-being attempting to turn everything that exists into non-existence. Sin is the way you and I contribute to evil.

Self-Justification and the fundamental lie

Now evil is real even if evil does not exist. Evil is real when it destroys truth with the power of the lie. What is the fundamental nature of that lie? Self-justification.

Just as our lungs are programmed to inhale oxygen at all cost, you and I inhale the good at all cost. If our bronchioles absorb polluted air, we cough. If our conscience absorbs sin, we lie. (Peters, Sin, 1993)

Start with something as simple as gossip. Around the soft drink machine, we employees gain a bond of unity when we are gossiping about the boss. The gossip tells us the boss is dirty, stupid, or immoral. By implication then, we feel clean, smart, and moral. [I think of gossip as a form of cursing.] It’s so easy. So natural. But, I ask, why do we do it? Because of our yearning to identify with what is good, just, and true.

This deep yearning for the good makes our sinning enigmatic. "Sin makes no sense...Sin, therefore, is radically unintelligible," observes Anglican theologian Cynthia Crysdale (Crysdale, 2019, p. 473). Here we are trying to make theological sense of something that otherwise makes no sense. Let’s begin with what we do virtually every day in gossip or, in some cases, making plans to commit violence.

We draw a line between good and evil and place ourselves on the good side

Recall Jesus’ parable of the Pharisee and the publican. Not ‘Republican’. Just publican.

And Jesus spoke this parable unto certain which trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and despised others: Two men went up into the temple to pray; the one a Pharisee, and the other a publican (tax collector).

The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican.

I fast twice in the week, I give tithes of all that I possess. And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me a sinner.I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other: for everyone that exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted (Luke 8:9-14).

Every day you and I are tempted to think like the Pharisee. In our private mind or in our political party, we draw a line between good and evil. Then, we place ourselves on the good side of the line. Once we find ourselves on the good side of the line, we breathe easily.

What’s wrong with that? This demonstrates that the human being is basically good, right? Whew!

Yes indeed, we humans are born with a thirst for what is good. Thank God. But it gets more complicated. Rather than discover God’s goodness, we scramble to paint ourselves in colors that everyone else, God included, will admire and say is “very good.”

After we draw the line between good and evil and place ourselves on the good side, we sometimes place somebody else on the evil side of that line. The Pharisee in Jesus’ parable placed the publican on the evil side. That is, the Pharisee scapegoated the publican.

“Only an evil person would ask a question like that.”

What does drawing a line between good ‘n’ evil for the sake of self-justification look like in our own era? Take a look at a press conference in Kerrville, Texas, on July 11, 2025. A woman who identified herself as a reporter from CBS News in Texas asked the 47th US president about the warning system for disasters in her state. "Several families we heard from are obviously upset because they say those warnings, those alerts, didn't go out in time. And they also say that people could have been saved. What do you say to those families?"

Note how POTUS responded by drawing a line between good ‘n’ evil and placing the reporter on the evil side of the line. “Only a bad person would ask a question like that, to be honest with you. I don’t know who you are, but only a very evil person would ask a question like that.”

In only a second, we have drawn a line between a good president and an evil reporter.

We scapegoat evil people so we can look good

Such rhetoric justifies you and me in behaving badly toward all persons we label ‘evil‘. Evil justifies us when we meet out punishment to those who deserve it.

There is a spirit of self-justification. Notice how gossiping with friends or co-workers we feel a group spirit, a bond in righteousness, a strength representing what is just.

With this sense that we are just, we think we have gained the right to punish. We think it is our task to rid the world of the scourge of evil on the other side of our line. No matter how cruel or viciously we behave, whatever evil we perpetrate is justified in our own minds. We feel innocent, powerful, victorious. In our own pursuit of the good, we become the force of non-being that leads to calumny, violence, and maybe even someone’s death.

You and I perpetrate evil only in the name of the good. What is the good? The right way to do things? God’s will? The security of our nation? Defeating other countries in war? Retrieving our national heritage?

The problem, of course, is that this is a lie we tell ourselves. It is the lie that supports self-justification. As already mentioned, the victim of our self-justification is called the scapegoat. We might even scapegoat God, or at least those religious bigots who believe in God.

Church preaching buttressed by discourse clarification tries to make self-justification and scapegoating transparent

It was self-justification on the part of the Roman and Jewish leadership that scapegoated Jesus. The Romans congratulated themselves for executing a potential terrorist. Members of the Sanhedrin congratulated themselves for punishing a blasphemer. The death of Jesus on the cross reveals to us just how the mechanism of self-justification combined with scapegoating works in every era and virtually every circumstance.

"Sin,” according to the late Brazilian theologian Vitor Westhelle, “in either individual terms or in socioeconomic and political systems that dominate, assimilate alterity or otherness resulting in exploited and colonized territories" (Westhelle, 2012, p. 82). Sin may take place within the human soul, but it also manifests evil in society.

The doctrine of sin when preached in Christian worship buttresses the gospel’s proclamation. You and I are relieved of the task of self-justification when we realize we are justified by God’s grace.

We would love it if Jesus turned out to be the final scapegoat in world history. But, alas, scapegoating continues night and day in our society.

What about public theology? What about the message of the church to the wider public? The doctrine of sin when articulated by the public theologian is like a giant fan. It blows away the smoke ‘n’ mirrors. It opens a space for truth beneath the gray fumes kicked up by ballyhoo, hypocrisy, self-justification, and scapegoating that dust coat every level of our society.

Conclusion

The gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. Part of its significance is that you and I are offered justification by God’s grace. We can accept Christ’s work to justify us within our faith. Or, we can resist it with self-justification. When we insist on justifying ourselves so we can look good, we are plugging our ears, making us deaf to the gospel.

When I look around, I see the enemy of the gospel just about everywhere in today’s political rhetoric. I wonder just who will be scapegoated next.

Substack ST 2035 What is the gospel? Part Five: The first enemy of the gospel is self-justification

SIN 1 Sin? Really?

SIN 2 Self-Justification

SIN 3 The Visible Scapegoat

SIN 4 The Invisible Scapegoat

SIN 5 Sin Boldly!

SIN 6 Sin and Grace

SIN 7 The true story of Satanic Panic

SIN 8 How can Satan cast out Satan?

SIN 9 Ted’s Tips on Satan and Demons

SIN 11 Sin-Talk and Grace-Talk

Substack ST 2031 What is the gospel? Part One

Substack ST 2032 What is the gospel? Part Two

Substack ST 2033 What is the gospel? Part Three

Substack ST 2034 What is the gospel? Part Four

▓

Meet Ted Peters. For Substack, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and emeritus professor at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Graduate Theological Union. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. He recently published. The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos blog site.

▓

References

Crysdale, C. (2019). Making Sense of Atonement: What Kind of Sense? Anglican Theological Review 101:3, 467-481.

Peters, T. (1993). Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Pieper, Franz Otto (1951). Christian Dogmatics, 3 Volumes. St. Louis MO: Concordia.

Westhelle, V. (2012). Eschatology and Space: The Lost Dimension in Theology Past and Present. New York: Macmillan Palgrave.