Nuclear Justice and Nuclear Weapons

Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran on nuclear weapons, nuclear power generation, and nuclear waste ONE

Nuclear fission! What a scientific achievement! In August 1945 two atomic bombs devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing perhaps 246,000 human persons. Yes, it ended World War II. But it also began a new era, the nuclear age in which we now live.

In the 1950s US President Dwight D. Eisenhower pressed for the development of “Atoms for Peace.” Nuclear power plants were built around the world, providing the delusion that electric power could be created and distributed cheaply. Radioactive spills at Three Mile Island in 1979, Chernobyl in 1986, and Fukushima in 2011 have alerted those of us living on Planet Earth that we are not safe with atoms for war or atoms for peace.[1]

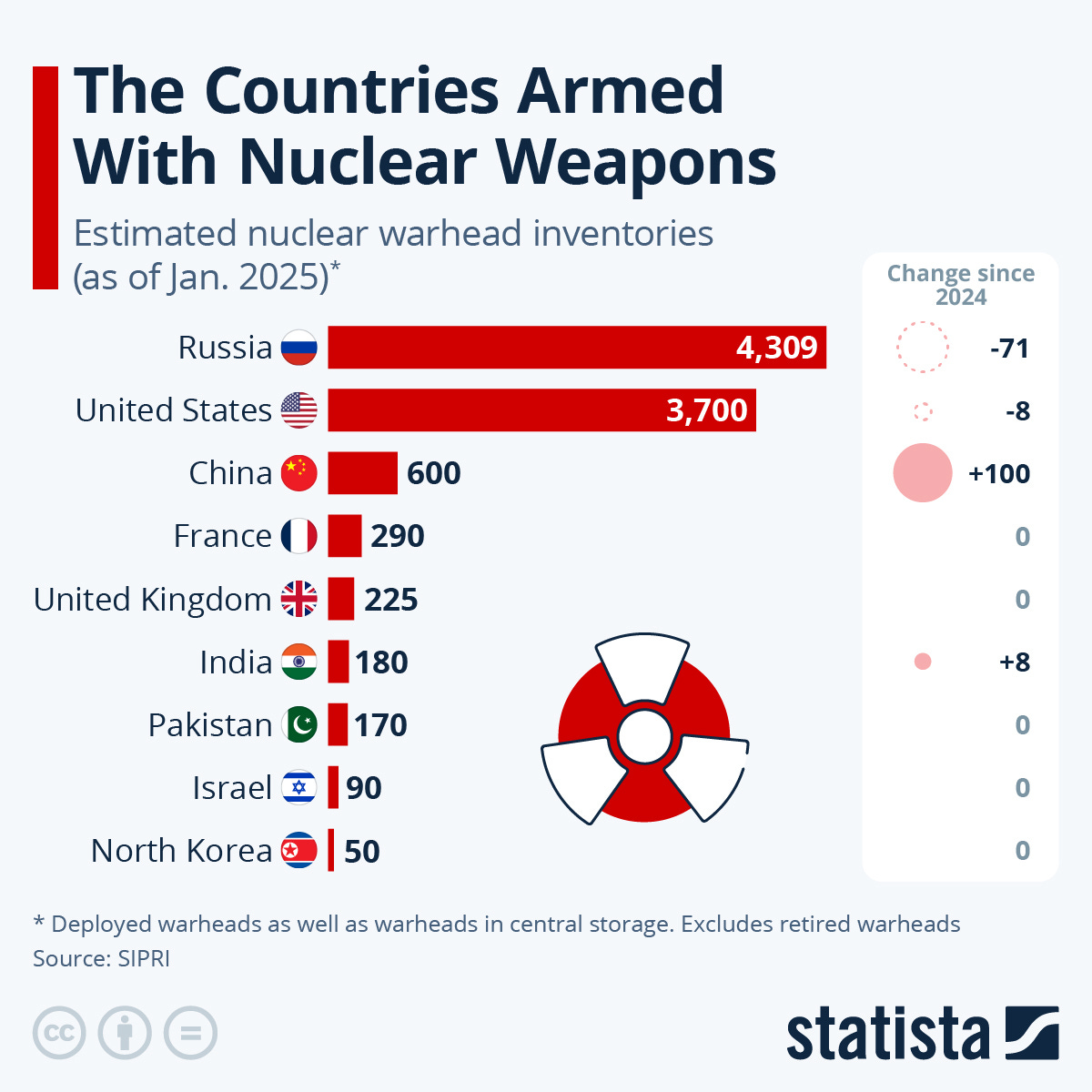

You may have thought that the Cold War ended in 1991 with the signing of the Belovezha Accords. We are safe from nuclear weapons now, right? So, why should we worry? In the fall of 2025, both the US and Russia ordered a restart of nuclear arms testing. Sojourners reminds us of the apocalyptic scope of the threat.

Nuclear weapons are the most destructive, inhumane, and indiscriminate weapons ever created. One large bomb detonated over a city could kill millions of people instantly. Following the initial blast, genetically damaging and cancer-causing radioactive fallout spreads among those exposed and into their future generations (Cortland and Hartung, 2026).

Here at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, our Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences has begun to assess the portents of nuclear fission for both war and peaceful energy production. Like so many other factors in the global ecological crisis, both scientists and public policy planners need to (1) understand possible, probable, and preferred futures; (2) decide which future is preferable; and (3) take the action necessary to control technology before anybody gets hurt.

Meet Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran

One of our gifted students already holds one doctorate in physics. Here in Berkeley he’s working on a second in theology. He has much to say on the topic of Nuclear Justice. So, let’s ask him to reflect on future possibilities which will affect all of us and even affect our descendants for generations to come. Professor Braden Molhoek recently introduced the man we nickname, “Tobi,” this way.

Dr. Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran (Tobi) has a PhD in nuclear radiation and health physics from the Federal University of Akure uh-KOO-ray. He is also a Ph.D. student in the Theology and Ethics department here at the Graduate Theological Union, where he has been able to also connect with faculty in the Nuclear Sciences Department at UC Berkeley. While he seeks to develop a constructive theology that is relevant for nuclear weapons and waste conventions in his current study, Tobi continues to advance his interests in nuclear peace advocacy, technological ethics, social justice, and radiation protection. He recently conducted a CTNS forum entitled, “Nuclear Justice, Peace, and Sustainability: Theo-Ethical Matters Arising.” The event was part of CTNS’ grant on Climate Science and Theological Education sponsored by the Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion (Doser) Program of the AAAS. He recently co-authored a book chapter focused on the future of AI impact on Africa (Akande and Ife-Adediran 2025).

In what follows, I will ask Tobi to address relevant questions.

1. I find it intriguing and exciting that you would bring your knowledge of physics and theological ethics into engagement. What do you mean by nuclear justice?

Nuclear justice is an ethical and social framework concerned with how the benefits of burdens of nuclear technologies -- especially energy, weapons, and radioactive waste -- are distributed across people, communities, generations and ecosystems, and whether those distributions are fair, accountable, and morally defensible.[2]

Nuclear justice requires decision-making to consider what is technically feasible and just. It incorporates different dimensions of justice, including distribution: who benefits and who bears risks; procedure: who gets to make decisions; intergeneration: what the current generation owes the future; and environment and ecology: how non-human life is affected by human decisions. Nuclear justice leverages foundational ethical theories in debates concerning uranium mining, nuclear weapons (non)proliferation, high-level nuclear waste handling, community consent and compensation, and ethical governance of long-term risks.

2. Nuclear arms proliferation! This frightens all of us. What do you recommend?

Given the mobility and contaminating effects of radioactive fallout, nuclear weapons can be considered as indiscriminate. They defy the just war principles of discrimination (targeting combatants, not civilians), and proportionality (achieving military good with the least possible harm). It is on this basis that the nuclear deterrence paradigm — the idea that nuclear weapons programs are implemented to demonstrate the capacity for retaliation in the case of aggression from adversaries —should not be absolutized. The accomplishment of the nuclear deterrence paradigm is that it maintains weapons balance (disincentivization of armed conflict between nuclear states) and nonproliferation. Even so, I ask for more. The deterrence strategy should play a transitional role towards global nuclear disarmament. Moreover, deterrence has been critiqued on moral grounds for its potential for mass destruction and utilization of fear to establish or sustain international order.

Disarmament should therefore be prioritized as a moral imperative and not only a policy preference or strategic option. Otherwise, future generations remain at the risk of the detrimental effects of radioactive fallout from the potential use of nuclear weapons. Nuclear governance has privileged elite strategic interests while externalizing its harm to marginalized populations.

Going forward, it is critical to center the voices of the most vulnerable and historically harmed in our ethical analysis, policy formulation, and decision-making. Testimonies from survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, communities affected by nuclear testing and uranium mining, and indigenous peoples whose communities have borne nuclear burdens should be taken seriously in creating a road map for the nuclear future.

Non-Conclusion ONE

Dr. Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran believes disarmament is the best way to secure a safe future for our children and their descendants. Nuclear justice requires nuclear weapons peace.

In their Sojourners’ article, Cortwright and Hartung remind us that faith communities in the 1980s were successful at persuading world leaders to limit weapons development. But we dare not rest. The New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) expires February 5, 2026. It is time for public theologians and the public witness of religious organizations to re-enter the fray of political conversation.

Yet, there is more. Even atoms for peaceful generation of electrical power pose dangers. Many of these dangers are unforeseen. One of the dangers is the siting of spent fuel rods and radioactive effluent discarded by nuclear power plants. To that dark cloud hanging over terrestrial civilization, we turn in our next post in this brief series.

Substack SR 1051. Nuclear Justice and Nuclear Weapons. Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran on nuclear weapons, nuclear power generation, and nuclear waste ONE

Substack SR 1052. Nuclear Justice and Nuclear Waste. Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran on nuclear weapons, nuclear power generation, and nuclear waste TWO

Visit our Patheos Science and Religion Resource Page

Theology of Nature Belongs within Public Theology

Substack SR 4003 Open Science, UNESCO, and Public Theology

Substack SR 4004 Defending Authentic Science against its Imposters: The public theologian should rally to protect the integrity of science

▓

Meet Ted Peters. For Substack, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and emeritus professor at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Graduate Theological Union. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. In 2023 he published. The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press. This year he has published an edited volume, Promise and Peril of AI and IA: New Technology Meets Religion, Theology, and Ethics (ATF 2025) and along with Arvin Gouw an edited collection, The CRISPR Revolution in Science, Religion, and Ethics (Bloomsbury 2025). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos blog site.

▓

References

Akande, Sunday, and Oluwatobi Ife-Adediran. 2025. “AI in African Liberation.” In The Promise and Peril of AI and IA: Technology Meets Religion, Theology, and Ethics, by ed Ted Peters, 289-302. Adelaide: ATF.

Cortwright, David, and William D Hartung. 2026. “ People of Faith Helped Stop Nukes; Let’s Do it Again,” Sojourners (January/February) https://sojo.net/magazine/januaryfebruary-2026/people-faith-helped-stop-nukes-once-lets-do-it-again.

Herzfeld, Noreen. 2025. “Call Me Bigfoot: The Environmental Footprint of AI and Related Technologies.” In The Promise and Peril of AI and IA: New Technology Meets Religion, Theology, and Ethics, by ed. Ted Peters, edited by Ted Peters, 131-150. Adelaide: ATF Press.

Peters, Ted. 5/2016. “A Waste is a Terrible Thing to Mind.” Theology and Science 14:4 391-392. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14746700.2016.1231974?needAccess=true.

Peters, Ted. 1982. “Ethical Considerations Surrounding Nuclear Waste Repository Siting and Mitigation,” .” In Nuclear Waster: Socioeconomic Dimensions of Long-Term Storage, by Steve H Murdock, Larry Leistritz, Rita R Hamm and eds, 41-56. Boulder : Westview Press.

Peters, Ted. 2/15/1989. “Not in My Backyard! The Crisis in Waste Siting.” Christian Century 106:5 175-177.

Peters, Ted. 3/10/1982. “Nuclear Waste: The Ethics of Disposal.” Christian Century 99:8 271-273.

Peters, Ted. 2022. “Theology of Nature Belongs within Public Theology.” Theology and Science 20:1 4-5; https://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/YB8U3WGA9J4S7T9CJRJB/full?target=10.1080/14746700.2021.2012914.

[1] Wolfgang Palaver, a theological interpreter of the world scene through the lenses of scapegoat theorist, René Girard, foresees a possible future in which the human species self-destructs. “Seit Hiroshima leben wir mit der Möglichkeit der Selbstauslöschung der Menschheit. Es gibt auch gute Gründe, sich vor Klimakatastrophe, Atomkrieg oder technologischen Risiken zu fürchten.”

[2] With the term “Nuclear Justice,” The United Nations gives special attention to mitigation of victimization from nuclear arms testing and radioactive fallout. The primary purpose of resolution A/C.1/80/L.57 on December 2, 2025 “is to establish the modalities for the first-ever international meeting on victim assistance and environmental remediation that will be held in early 2026. This resolution provides a basis for the Secretary-General of the United Nations to invite Member States, Observer States, Observers, Civil Society, Academia, Scientists, and affected communities to participate in the meeting.” Watch for action later in 2026.

Outstanding work bridging nuclear physics with ethical theology. The insight that deterrence serves a transitional role rather than an end state is crucial, because it reframes the moral problem. I worked briefly with a non-profit on waste managment issues, and what stuck with me is how much current nuclear govrnance does privatize gains while socializing harms across generations. The real challenge though is creating verification mechanisims during disarmament that dont just replicate elite decision structures.