Since my sophmore year in college the question of free will has bugged me. I was invited by one of my favorite professors to join an advanced philosophy course on the topic. When on the first class meeting I announced that I believed in free will, everyone in the class turned to frown at me. Both the professor and students posited at the outset that free will is a delusion. The only remaining question had to do with which kind of determinism dominates: nature or nurture? I felt embarassed because my naivete had been exposed.

Today I still persist in my delusion. Why? Because I experience making free decisions all day long. Right now, writing this post, I am deliberating between alternative things to say, deciding which alternative to actualize, and typing what I freely decide to say. It seems to me that the task of the philosopher is to explain free will, not explain it away.

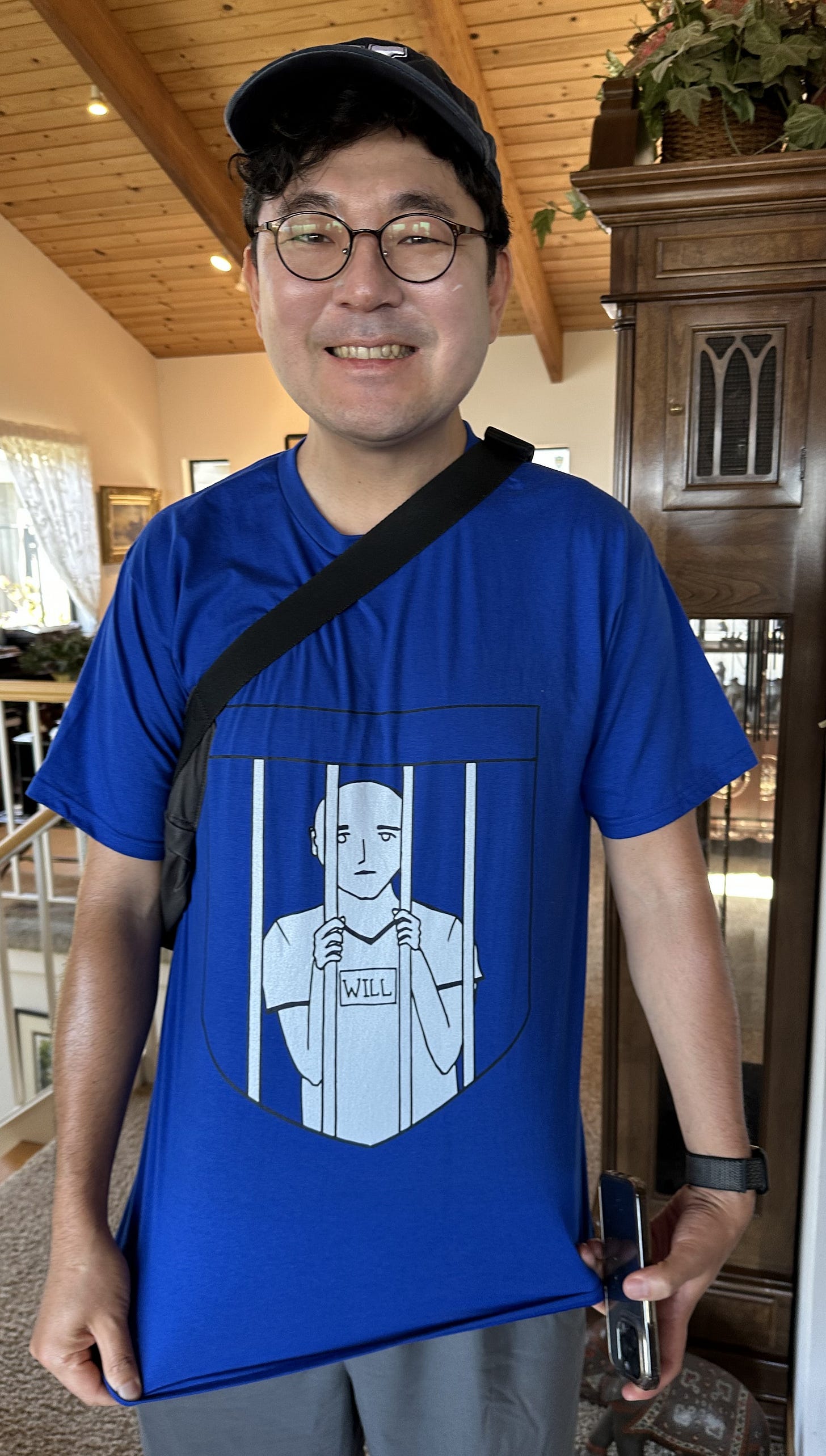

In a moment you’ll meet Chang In Sohn. In Berkeley we call him Chan. Chan is a most interesting young man. He’s an experimental researcher in the field of neuroscience. As a scientist, he’s a determinist. He thinks science provides evidence that proves determinism. So, Chan wears a tee shirt with free will in jail.

Meet Chang In Sohn.

Chan is a Newhall fellow at the Graduate Theological Union and a Charles H. Townes Graduate fellow at the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences. He is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the theology and ethics department, with a concentration on theology and science. Already as an undergraduate in Korea, he took an interest in the intersection between Christian theology, moral philosophy, and neuroscience. At the University of California, Berkeley, Chan is engaged in laboratory research on primate brain activity. His larger project deals with metacognition that incorporates theological anthropology, Western moral philosophy, evolutionary studies, and the neural representation of metacognition and self-awareness in neuroscience.

So, let’s ask Chan to weigh in on the question of free will.

1. Why do you wear a shirt with free will in jail?

Chang In Sohn writes. This is my class t-shirt for UC Berkeley’s neuroscience course titled, Neuroscience, Film, and Philosophy. This course is instructed by Dr. Doris Tsao, one of the prominent visual neuroscientists in the world (she won the Kavli prize for neuroscience this year, often called a precursor to the Nobel Prize), and I have the privilege to serve as a teaching assistant since spring 2023 and more than a year in her lab as a visiting doctoral researcher and a lab manager position.

The course aims at the intersection between neuroscience and philosophy, with the film as a popular culture medium. One of the primary topics covered in this course is a matter of free will – whether free will exists or not. The course covers different positions, from libertarian free will to hard determinism, and settles with a soft determinism/compatibilist position, somewhat in the middle of the spectrum. Compatibilism argues that we can still act as free, morally responsible agents, even if our desires are determined. The guy named “Will” in the t-shirt indicates free will – free will is not free as we presuppose. While many people who believe in human freedom probably don’t like the conclusion, at least we did not execute Will!

2. What is the nature of your research in neuroscience? What are your findings?

Chang In Sohn writes. Free will is not exclusively a neuroscience topic. It requires philosophers to intervene. Neuroscientists, therefore, focus on what they can do best: examination of the brain during the decision-making process. Note that there is no clear division between “deterministic” hypothalamic circuits and “free” cortical circuits, but each brain region operates with inputs and outputs of neural computations. Yet, neuroscientists found several key findings that are relevant to the ongoing discussion of free will. Here are some key examples covered in the course:

1) pathological evidence: when brain damage erases, distorts, or creates “will”

Hemispatial Neglect syndrome: Patients with parietal lobe damage ignore one side of space yet act with a feeling of volition, which shows a disconnection between the feeling of agency and actual control. In other words, the feeling of volition operates even without a massive loss of environmental information and self-knowledge.

Alien hand syndrome: Supplementary motor area (SMA) lesion. Patients’ limbs move “on their own” despite the person recognizing the limb as theirs, which demonstrates that agency can be neurologically disintegrated. (Biran & Chatterjee, 2004)

Case of Charles Whitman (1966): subcortical limbic pathology influences moral restraint and decision control, reinforcing the brain-dependence of “choice.” In Charles Whitman’s case, his meningioma compressed the amygdala and hypothalamus, which escalated rage and violence.

2) Brain stimulation & optogenetics: when scientists incite urges or actions

Electrical stimulation of the pre-SMA region (fronto-medial motor cortex): The pre-SMA region is a key structure for voluntary movement; in humans, direct electrical stimulation of the pre-SMA region produces an urge to move, and stronger stimulation results in action. At the same time, pre-SMA lesions in the monkey can inhibit the self-initiation of action or lead to uncontrolled actions. In Fried et al. (1991), scientists stimulated the subjects, who reported an urge to move and sometimes partial movement; higher electrical stimulation evoked carried out action as well as conviction that “I decided to do that”(Fried, et.al., 1991).

Optogenetic drive of VMHvl mice (Li et al., 2017): when stimulated in the Ventro-medial hypothalamus, mice exhibit object craving actions – they exhibit compulsive object-licking whenever light is on, and their behavior stops when light turns off. But when stimulating the anterior hypothalamic area, the mice suddenly showed aggression; the tame mouse suddenly assaults a neutral conspecific or an inanimate object when light is on. This experiment shows that innate motivational states (desires, including object craving and aggression are based on circuit activation and can be initiated by stimulation, while undermining the intuition that choices spring from a unitary rational self)(Li, et.al., 2017).

3) Pre-decision neural signatures: when the brain acts before you are consciously aware

Time of Conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (Libet et al. 1983): Libet’s article states that the brain initiates the will to move and consciously makes voluntary movements long before we are even consciously aware of that will (Libet, et.al., 1983).

However, I also interpret the veto moments in Libet’s article as one of the strongest claims to support the compatibilist free will position: even if our decisions are byproducts of unconscious neuronal processes, there is room for us to execute conscious, reflective intervention to alter the final decision.

Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain (Soon et al., 2008): the aided prediction of the frontopolar and parietal cortex to predict a motor decision is available 7-10 seconds before the decision is consciously made, with approx. 60% accuracy (Soon, et.al., 2008)(Soon, et.al., 2013).

Internally generated preactivation of single neurons in human medial frontal cortex predicts volition (Fried et al., 2011): volitional processes are not triggered instantaneously at the point of conscious awareness, but there is a preconsciousness neuronal build-up period in the brain within milliseconds or even 1 – 1.5 seconds before the urge is reported. Especially, a particular combination of a few hundred neuronal activities can predict a decision about 700 milliseconds before the subject consciously feels that they decided, with more than 80% accuracy, indicating that our awareness of will actually occurs at a later stage of events (Fried, et.al., 1991).

4) Decision-making paradigms: how evidence turns into choice

Random-dot motion task (Shadlen and Newsome 1996; Roitman and Shadlen 2002): The Dot motion task can be considered a microcosm of decision making writ large. Based on this task, neural recording occurs within this sequence: MT (motion evidence) > LIP/FEF (accumulator) > superior colliculus (motor). Single LIP neurons ramp upward as moment-by-moment evidence arrives; steep slope = motion strength. This experiment shows that choice and timing of the RDM task can be predicted from neural activity hundreds of milliseconds before the saccade – the behavioral “decision” is simply bound-crossing in a drift-diffusion process (Shadlen & Newsome, 1996)(Roitman and Shadlen, 2002).

Hippocampal replay: a mechanism to stimulate different future outcomes: food-restricted rat in a W-shaped maze. When an animal pauses, CA1 place-cells fire compressed “replay” sequences, and simultaneous ventral-striatum recordings show a dopamine-like value signal tagging each replayed path. The result shows that replay occurs before the actual turn and predicts which side the rat will choose, which may indicate that deliberation is an internal model-based search based on value, as a form of mechanistic computation. Related experiment done by Jadhav et al. 2012 showed that disrupting this hippocampal replay computation results in a collapse of choice. A trajectory that the rat has never encoded cannot be replayed during a replay, and therefore cannot be selected as an option. “Free will” is not an ocean of infinite possibilities, but a combinatorial search within the limited space carved out by synaptically stored experience (Pfeiffer & Foster, 2013).

3. Does Christian theology have anything at stake in the debate over free will?

Chang In Sohn writes. Yes. I think the stakes are both theological and pastoral. At a theological level, Christian theology has never portrayed human beings as wholly self-determining with free will. Mainstream theology, from Augustine’s Confession to Martin Luther’s Bondage of the will, has insisted that the fall shackled human freedom, disrupting our desires away from God. Preserving human freedom while addressing the classic problem of divine omnipotence and omniscience has been a task for classical Christian thought. Yet the tradition simultaneously proposes that humans remain genuinely responsible – freely able to accept the gospel, to repent, and to cooperate (or not) with grace.

Modern neuroscience intensifies this tension by revealing how our choices are byproducts of neural circuitry shaped by genetics, experiences, trauma, habit, and environment. If our decision can be reduced to ramping activity in pre-SMA regions or to hippocampal replays, how can the traditional doctrine of culpable sin and transformative redemption still stand? Christian theology needs to address this tension, and should incorporate neuroscientific findings in this topic.

At the same time, pastorally, the stakes are tangible. Determinism may lead to fatalism and resignation, whereas communities that believe choices matter cultivate hope, discipline, and responsibility. Again, classical Christian thought has embraced two truths at once: God is the sustaining first cause of every creaturely act, while creatures exhibit true secondary actions to express their formed character, desires, and motivations. This framework fits well with a compatibilist understanding. Mechanistic description of how desires and deliberations arise in brain circuits need not erase responsibility. As Libet presents, there is room for us to execute conscious, reflective intervention to alter the final decision, even if most of our unconscious actions are driven by our unconscious neural processes.

4. Are you an incompatibilist or a compatibilist? Why?

Chang In Sohn writes. I identify myself as a compatibilist, for both empirical and theological reasons. This compatibilist, soft deterministic freedom argues that freedom is real but limited. Christianity has been taught that the will is finite, historically situated, and distorted by the fall, yet still capable of genuine response.

Modern neuroscience and evolutionary psychology can sharpen, rather than dissolve, what Christianity has been arguing. Current science shows that what we call “free will” emerges from layered neural computations: hypothalamic drives, hippocampal replay, and prefrontal evaluation.

The evolutionary process selected these systems because of survival benefits and behavioral flexibility. Then culture and society, based on the collection of individual brain systems, amplify them through language and symbol. In this sense, human freedom is an environmental and evolutionary byproduct – a bottom-up development that produces top-down behavioral control. Such emergent freedom remains limited and fragile, and thus corresponds to the fall. Our neural architecture, like the rest of creation, is subjected to fall. However, such free will is a development through the creature’s own motivational hierarchy rather than an external coercion (not as given feature directly and completely by God); thus, creatures remain genuinely responsible.

In other words, the fall is not an event that eradicated agency but one that distorted the motivational architecture through which agency is exercised. Neuroscience points out some of the phenomena of such distortions in physical terms: a hyperactive amygdala incites rage and violent actions, a dopamine system calibrated by addictive loops, a thinning prefrontal cortex due to constant exposure to a stressful environment, or a whole brain structure easily swayed by external stimuli (lust, seduce, etc.).

The Scripture names the same reality as hamartia – a distortion of the self toward disordered ends. I am not saying that sin is completely reducible to those physical terms, but I can say that sin “in the flesh” also has similar connotations to say some results of sin are “in the neural circuitry.”

Yet, because freedom is a naturally evolved capacity, it is stable enough to anchor morality. God granted human freedom to listen, believe, and cooperate (or not) with grace. The Spirit can intervene synapses, reshaping patterns of attention and desire until new convictions become actual actions. If this is the case, redemption is God’s gracious reformation of that very circuitry easily subject to sin. The orders of creation and redemption interlock – evolution grants a freedom, which is real but limited, and redemption heals that freedom so creations can attain their telos in love of God and neighbors.

In conclusion, neuroscience does not undermine the Christian doctrine of sin, fall, and redemption; it offers a concrete grammar for describing how freedom is finite, dependent, and limited, yet still authentic enough for sin to be blameworthy and for redemption to be the hope that all creatures are waiting for.

5. What else would you like to say?

Chang In Sohn writes. I will clarify my definition here: Freedom is acting from one’s own internal states without external coercion. A choice is free when it arises from the agent’s own architecture, the brain, which processes and values such desires, beliefs, memories, evaluative standards, etc, without being bypassed or overridden by an external force, even though that architecture itself is fully caused.

Again, we do not transcend causal networks, a cortical structure that receives and creates our own value system, a development throughout millions of years of evolution. But what I want to highlight here is that predictability is not equivalent to freedom – a drift diffusion model or hippocampal replay may forecast what I may do several milliseconds in advance, but my conscious motor plan is still mine; the forecast only reflects the transparency of my neural dynamics, not my conscious, reflective, and autonomous choice of action. Instead, what would undermine freedom is an external force that takes away control of it – chemical sedation, brainwashing propaganda, or pathology.

Therefore, freedom becomes neither libertarian metaphysical magic nor nihilistic determination, but the lived reality of embodied creatures whose choices manifest the experiences and values in their brains.

Substack SR 1021 Chang In Sohn, Our Brains, and Free Will

Substack SR 1020 Anselm Ramelo, AI, and Free Will

Substack SR 1021 Chang In Sohn Puts Free Will in Jail

Patheos SR 1022 Is our free will really in jail?

Patheos SR 2002 Did I lose my conscious mind to science?

Patheos SR 2003 Did I lose my free will to science?

Patheos SR 2004 Did I lose my inborn sense of God to Atheism?

Patheos SR 2005 Did I lose my self to my brain?

Patheos SR 2006 Did I lose my self to determinism?

Patheos SR 2007 Did I lose my self to Christian freedom?

Works Cited

Biran, I., & Chatterjee, A. (2004). Alien hand syndrome. Archives of Neurology, 61(2), 292–294.

Fried, I., Katz, A., McCarthy, G., Sass, K. J., Williamson, P., Spencer, S. S., & Spencer, D. D. (1991). Functional organization of human supplementary motor cortex studied by electrical stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience, 11(11), 3656–3666.

Li, Y., Mathis, A., Grewe, B. F., Osterhout, J. A., et al. (2017). Neuronal Representation of the Social Network in the Lateral Hypothalamus. Nature, 550(7675), 388–392.

Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to the onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). Brain, 106(3), 623–642.

Pfeiffer, B. E., & Foster, D. J. (2013). Hippocampal place-cell sequences depict future paths to remembered goals. Nature, 497(7447), 74-79.

Roitman, J. D., & Shadlen, M. N. (2002). Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area during a combined visual discrimination reaction-time task. Journal of Neuroscience, 22(21), 9475-9489.

Shadlen, M. N., & Newsome, W. T. (1996). Motion perception: seeing and deciding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 93(2), 628-633.

Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H.-J., & Haynes, J.-D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), 543–545.

Soon, C. S., He, A. H., Bode, S., & Haynes, J.-D. (2013). Predicting free choices for abstract intentions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 110(15), 6217–6222.